In a recent excavation in Jerusalem, archaeologists delving into the remains of a structure dating back to the First Temple period made an intriguing discovery. Within one of the rooms, they uncovered the well-preserved skeletal remains of a small pig, estimated to be around 2,700 years old. The creature appeared to have met its demise under the weight of collapsing debris during an enigmatic event that inflicted substantial damage on the entire building.

Further exploration of the same room revealed a diverse array of animal skeletons, including those of cattle, goats, sheep, fish, birds, and gazelles. Notably, many of these bones exhibited signs of cutting and burning. Alongside the animal remains, archaeologists unearthed numerous large storage vessels and small cooking pots, shedding light on the possible culinary and storage practices of the inhabitants during that period.

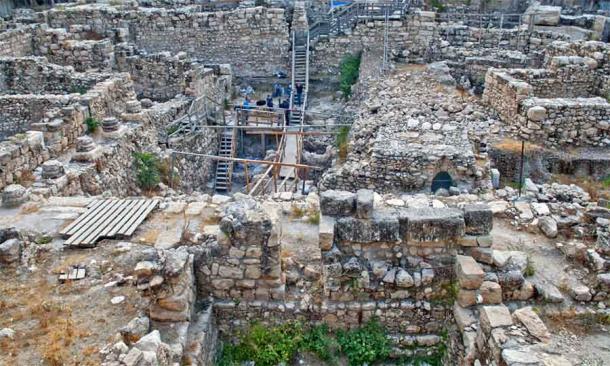

First Temple period structures near the Gihon Spring in Jerusalem’s City of David, where the pig skeleton was found along with the “butchered” remains of many other types of animals. (Joe Uziel / Israel Antiquities Authority)

Pig Skeleton Suggests Pork Was On the Menu in Jerusalem

Collectively, these findings unveil a practice of on-site animal slaughter and butchering for culinary purposes among the ancient residents of Jerusalem in the First Temple Kingdom of Judah. While the small pig eventually seemed destined for the menu, its demise coincided with the destruction of the building, brought about by an unidentified force (with no recorded earthquake in Jerusalem during that time).

The significance of this discovery lies in the fact that the consumption of pigs and pork is explicitly forbidden in the Jewish faith according to the laws of Kashrut, derived from the Old Testament books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy. These laws dictate that only animals with cloven hooves and those that chew their cud are deemed suitable for consumption, effectively excluding pigs.

The revelation that this prohibition was seemingly disregarded raises questions about the culinary practices of the inhabitants. It remains uncertain whether this deviance from dietary restrictions was an uncommon occurrence or a more prevalent behavior.

“It appears that this articulated pig may be evidence that although pork was largely not consumed in Judah and Jerusalem, this was not necessarily based on a very strict taboo. The extent of culinary consumption based on laws of Kashrut in the Iron Age is still debatable,” noted co-authors Lidar Sapir-Hen, Joe Uziel, and Ortal Chalaf, Israeli archaeologists leading this discovery, in an article prepared for the journal Near East Archaeology.

Pig remains, including the articulated skeleton in question, constitute approximately two percent of the animal remnants discovered in First Temple-period excavations in the city of Jerusalem. While this percentage is relatively low, it challenges expectations if strict adherence to dietary prohibitions were the norm.

An archaeologist retrieves the skull of a piglet from a First Temple period building in Jerusalem’s City of David at the site where the “articulated” pig skeleton was also found. (Joe Uziel / Israel Antiquities Authority)

Religious Rules vs. the Privileges of Wealth

Interestingly, the archaeologists uncovered compelling evidence indicating that the building housing the pig remains belonged to an affluent family, serving as their residence.

Comprising four rooms constructed from rough field stones, the dwelling yielded a trove of valuable personal artifacts during excavations. Among these discoveries were pieces of exquisite jewelry and an intricately carved human figurine. Situated near the Gihon spring, Jerusalem’s primary source of fresh water during that era, the location added prestige to the property.

While initially identified as a private residence, the building may have had additional functions. Notably, one of the rooms yielded an ancient stamping device known as a bulla. These flat stones bore the markings of city or regional administrators, responsible for affixing their official seal of approval to crucial documents or valuable items. The presence of the bulla suggests that the residence likely belonged to a significant public official, whose seal carried legal recognition.

Given that the room where animals were slaughtered and butchered was part of a privately owned space, there’s a possibility that the owners clandestinely engaged in the consumption of pigs. Alternatively, it’s conceivable that their activities were known, but the family, owing to their wealth and influence, managed to escape scrutiny.

If the latter scenario holds true, it would align with a recurring historical pattern where societies, both past and present, exhibit a dual set of rules—one for the affluent elite and another for the general populace. Ancient Jerusalem, it seems, might have adhered to such a stratified system.

The Givati Parking Lot excavations in the City of David Park in Jerusalem, a site where remnants of the 586 BC destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians were discovered. It was at this site that the pig skeleton and other animals remains were discovered. (Shai Halevi / Israel Antiquities Authority)

How Much Did the Bible Really Matter in First Temple Jerusalem?

Another perspective, presented by study co-author Lidar Sapir-Hen, introduces a different possibility. Sapir-Hen suggests that the scarcity of pigs in most regions of the Ancient Near East during that era might have played a more pivotal role in restricting their consumption than adherence to Biblical prohibitions.

To support this hypothesis, he highlights the limited presence of pig remains in excavations at Late Bronze Age sites, dating back to the second millennium BC. This observation gains significance as the Bible, constituting the Old Testament, was authored much later during the Iron Age, in the first millennium BC.

Sapir-Hen’s proposition implies that the scarcity of pigs, rather than strict religious taboos, could have influenced the dietary practices of ancient communities in the region. This alternative explanation challenges the conventional understanding of the constraints on pig consumption during that historical period.

Moreover, Sapir-Hen points out that pig remains are infrequently uncovered at Iron Age sites across the broader region. Excavations associated with ancient civilizations such as the Canaanites, Phoenicians, Arameans, and Philistines yield scant evidence of regular pig meat consumption.

It appears that pig populations were generally low throughout the Ancient Near East, resulting in the uncommon consumption of pig meat.

Addressing the issue of Biblical prohibitions, contemporary scholars tend to believe that the Old Testament took its recognizable final form during the era of the Second Temple, spanning from 516 BC to 70 BC. While certain parts were composed in the First Temple period, the majority of the text was finalized later.

Studies indicate that religious practices in the First Temple kingdoms of Israel (north) and Judah (south) exhibited diversity and eclecticism, varying from one location to another. Consequently, the adherence to Biblical rules, as understood today, was not universally consistent. This variability may extend to rules against consuming pigs, which might not have been firmly established during that time or were not universally adhered to even if they existed.

If scarcity, rather than religious mandates, restricted the widespread consumption of pigs in the Iron Age Kingdom of Judah, their meat could have been considered a luxury. Pigs might have been relatively expensive, making their meat an affordable indulgence only for the wealthiest citizens of Jerusalem. This rationale could explain the discovery of the pig skeleton in the residence of an elite member of ancient Jerusalem society, as indicated by the recent archaeological study.

Top image: The “articulated” pig skeleton found in an ancient dig site just outside of Jerusalem, Israel, suggesting that pork was on the menu for some for a period of time in the First Temple period. Source: Oscar Bejarano / Israel Antiquities Authority

By Nathan Falde